Be yourself; Everyone else is already taken.

— Oscar Wilde.

This is the first post on my new blog. I’m just getting this new blog going, so stay tuned for more. Subscribe below to get notified when I post new updates.

Be yourself; Everyone else is already taken.

— Oscar Wilde.

This is the first post on my new blog. I’m just getting this new blog going, so stay tuned for more. Subscribe below to get notified when I post new updates.

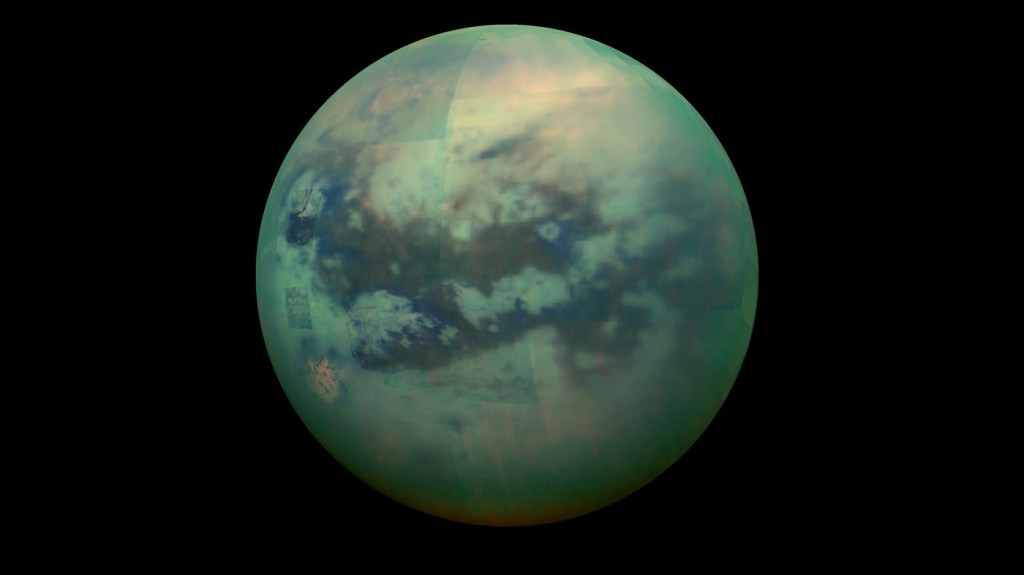

Could human beings inhabit Titan, one of Saturn’s moons? Titan is one of the least hostile places for humans in the outer solar system. Titan has liquid methane lakes and oceans on its surface, and even has weather. Titan’s atmosphere is very dense – 95% nitrogen and 5% methane. The gravity on Titan is slightly weaker than the gravity on the moon. The pressure is quite similar to that on Earth. This very interesting article explores the possibility on living on Titan or Enceladus, another one of Titan’s moons.

Scientists are investigating if methane based life exists on Titan. If a human being was on titan, they would only need an oxygen mask and protection from the weather. Could humans inhabit titan some day?

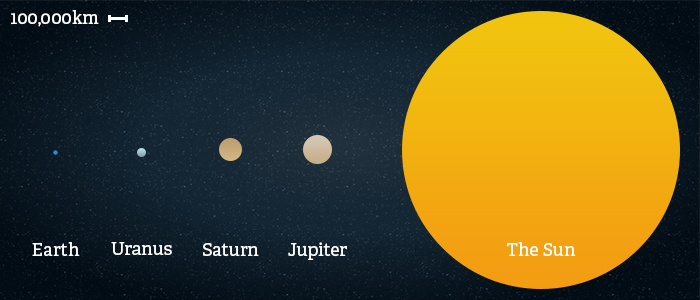

Okay, hear me out – Mercury is the closest planet to every other planet in the Solar System, on average. When I read this it kind of blew my mind but after reading this article it makes a lot of sense. This is true because Mercury is on a very tight orbit around the sun. The other planets, because of their much larger orbits, spend a lot of time very far away from each other. Therefore, Mercury is the closest planet to all the other planets! The article hyperlinked above has a model that shows this quite clearly. The man runs a model over 10,000 years and calculates the distances each day and averages them out to find that Mercury is the closest planet to Earth around 45% of the time, Venus is 35% and Mars is the closest 20% of the time.

Source: space.com

Learning about the planets in our last few classes (RIP senior year) reaffirmed for me that the earth is indeed very small compared to the other planets in the solar system. But then I read that 99.8% of the mass in the solar system is still contained within the sun! Even though the gas giants are so massive, they’re still so small compared to the sun, and then the sun is an average size star with some stars up to 100 times bigger.

After every class, I feel deeply humbled by how small we are in the grand scale of things. But sometimes I read statistics like this that provide a new angle to appreciate just how much larger other objects are in the universe.

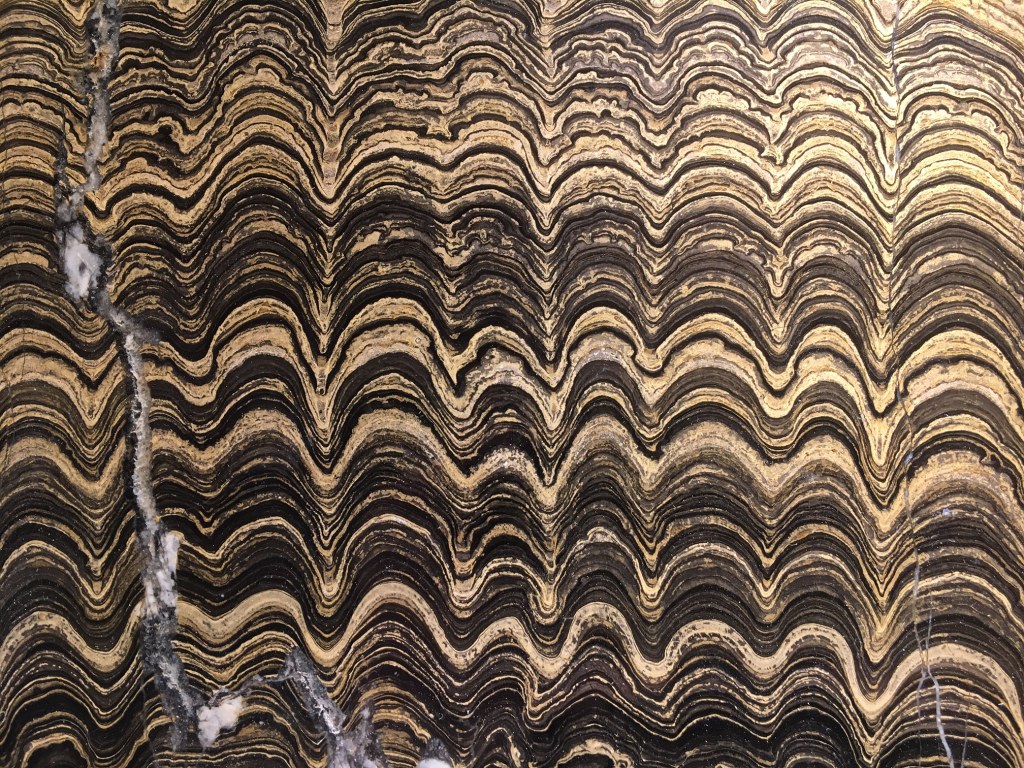

Stromatolites are layered mounds or sheet-like layers of sedimentary rock that were originally forced by growing on a layer of cyanobacteria, a single-cell microbe. Fossilized stromatolites provide a record of ancient life and tidal patterns on Earth.

Millions of years ago, seas all over the world would resemble the picture above, which was taken from Shark Bay, Australia. This unique pattern was created through a process of accumulation of calcium carbonate and the depletion of carbon dioxide in the water.

Cyanobacteria, which resulted in the creation of stromatolites, were one of the first organisms on Earth. Certain kinds of cyanobacteria are 3.7 billion years old. They produced oxygen as a by-product of photosynthesis, which made it possible for more complex life forms to evolve in our oceans.

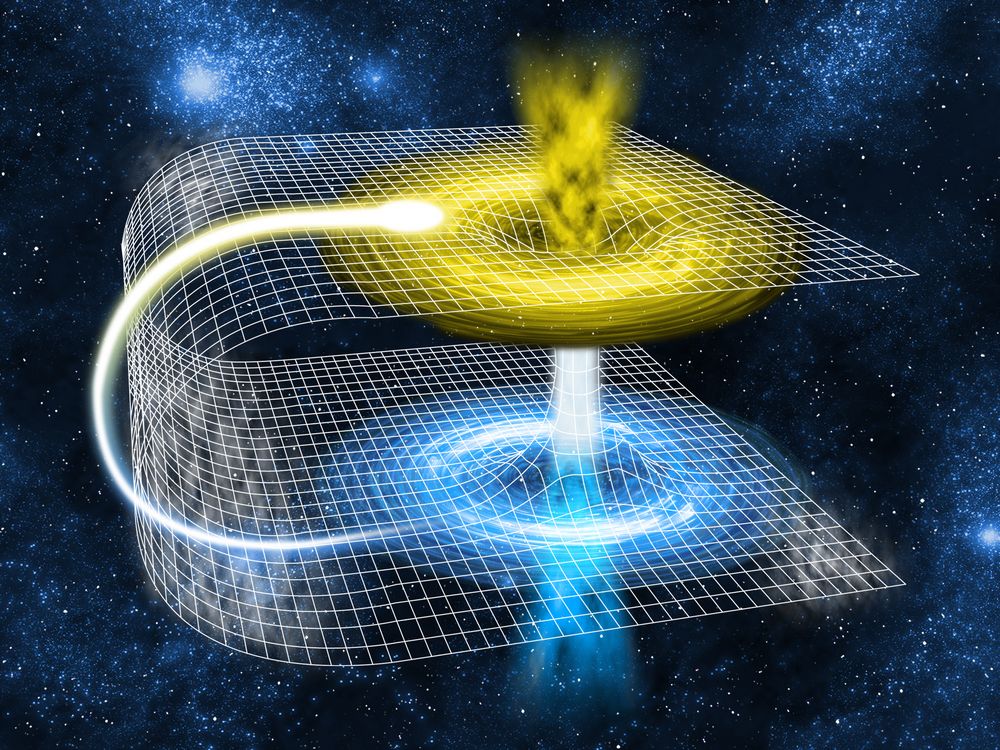

Reading about the vast size of the universe, I started exploring the possibility of travelling through the it. One popular theory on the structure of space-time is a wormhole. It postulates a theoretical passage through space-time that could create a shortcut to a different spot in the universe. So far, we’ve thought about travelling in a linear fashion. A simple way to think about wormhole travel is folding a paper in half and travelling from one end to the other by poking a hole through the middle. The image below is a good way to visualize it. There is debate about whether wormholes can actually exist. We are definitely very far from actually observing a wormhole, but scientists are exploring the possibility of their existence.

For my first blog post, I chose this picture of me and my friend after climbing our first 14er in Colorado over the summer. As a first time climber, the climb was extremely challenging. A description of the climb can be found here.

I chose this picture because I think it represents how I felt about the universe after the first class. Like the view from the top of the mountain, the universe is beautiful and inspiring. However, it is also a reminder of how small we are in the grand scheme of things.

This is an example post, originally published as part of Blogging University. Enroll in one of our ten programs, and start your blog right.

You’re going to publish a post today. Don’t worry about how your blog looks. Don’t worry if you haven’t given it a name yet, or you’re feeling overwhelmed. Just click the “New Post” button, and tell us why you’re here.

Why do this?

The post can be short or long, a personal intro to your life or a bloggy mission statement, a manifesto for the future or a simple outline of your the types of things you hope to publish.

To help you get started, here are a few questions:

You’re not locked into any of this; one of the wonderful things about blogs is how they constantly evolve as we learn, grow, and interact with one another — but it’s good to know where and why you started, and articulating your goals may just give you a few other post ideas.

Can’t think how to get started? Just write the first thing that pops into your head. Anne Lamott, author of a book on writing we love, says that you need to give yourself permission to write a “crappy first draft”. Anne makes a great point — just start writing, and worry about editing it later.

When you’re ready to publish, give your post three to five tags that describe your blog’s focus — writing, photography, fiction, parenting, food, cars, movies, sports, whatever. These tags will help others who care about your topics find you in the Reader. Make sure one of the tags is “zerotohero,” so other new bloggers can find you, too.